Does autumn sun ‘kill 28 drivers per year’?

October 3, 2014

Autonomous Vehicles – Tomorrow’s World?

October 23, 2014Vision Zero - Why F1 has one and we don't

Anyone who knows me is probably aware that I am an avid F1 fan. I personally don’t think being a motorsport fan and being a road safety professional are in any way at odds – the controlled environment of a race track, driven by the most talented drivers in the world, with rules and regulations closely obeyed, the best medical personnel on hand who are assisted by marshalls and race officials is polar opposite to the daily situations experienced on the roads by you and I.

It’s been nearly two weeks since Jules Bianchi had his huge accident at Suzuka, Japan and he is still fighting for his life. At the race in Russia, there had been a great deal of talk about what can be changed to make this sport safer. It’s got me thinking about how attitudes to safety, acceptable risk levels and use of data differ at the two ends of the motoring spectrum: Formula 1 compared to the normal member of the public using the roads daily.

The reaction of the F1 world to this incident has universally been that, ‘this cannot be allowed to happen again’. No-one can deny that motorsport is dangerous. Warnings are printed on the back of tickets and signs reminding us of the dangers are clearly displayed at each track. The enormous pay scales reflect the level of risk to drivers as well as rewarding their talents. Yet even with the acknowledgement that 22 drivers heading towards the first corner at speeds of up to 200mph is dangerous, death and serious injury is not something the F1 world is willing to accept.

They have their own version of ‘Vision Zero’ and believe that everything should be done to ensure that serious crashes are prevented.

The circumstances leading up to Bianchi’s crash were pretty unique. Racing in wet weather, the deployment of safety cars, the use of yellow flags and the removal of crashed or stopped cars by recovery vehicles are all common occurrences in F1 but just not necessarily all at the same time. This could therefore be deemed a ‘freak’ accident. Nevertheless, the F1 world has come together to gain an understanding of how this crash occurred and what can be done to prevent it from happening again.

This is where we can draw some parallels with general road safety. Rather than adopting the Vision Zero approach, we tend to undertake trend analysis and look for clear links between contributory factors and potential solutions. We are aware of ‘statistical blips’ and like to use data for collisions over a number of years in order to remove outliers or seasonal variations. It means that we can base our interventions on sound foundations but how many times have members of the public asked us “how many people need to die before something is done?” whereas in the F1 world every incident is analysed to see what can be learnt.

However, I think one area where we could learn from the F1 world and their approach to achieving a Vision Zero is in the way in which they work together to improve safety. Whilst there are many great road safety partnerships up and down the country, perhaps there are opportunities for us to work even closer together and to make sure all stakeholders participate. The parties involved in F1 are analogous to the road safety profession in many ways:

- At the top is the FIA (the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile) who are the governing body for motor sport and regulates the sport in a similar way to how the Government is legislator of traffic law and provider of national road safety guidance.

- Each circuit is owned by a body separate to the FIA and the track owners are responsible for the tarmac in a similar way to local highways authorities are responsible for our roads.

- At each race, there are stewards who have the power to impose a variety of penalties on drivers if they commit an offence during a race. Offences can include speeding in the pit lane, causing an avoidable accident, unfairly blocking another driver or jumping the start and are applied for both sporting and safety reasons. In our world, this role is performed by the police and the courts.

- At the scene of crashes, track marshalls and recovery vehicle drivers (both are often volunteers) perform the dangerous task of removing debris and vehicles to clear the circuit for racing. This could be seen as a similar role as that performed by the fire and rescue service when rescuing casualties and clearing the roads so that traffic can pass.

- F1 car manufacturers and road car manufacturers obviously both have a clear interest in designing safe vehicles, although road car manufacturers seem to work in isolation in comparison to F1 car designers. There are also the F1 teams who have a clear interest in safety and perhaps these represent the family and friends of drivers. In the wake of Bianchi’s accident, the FIA, the owners of the Suzuka circuit, the teams and the vehicle manufacturers are all working together in a way that perhaps is more co-ordinated than in our road safety world.

Perhaps there are ways in which the Department for Transport could co-ordinate closer co-operation between all of the stakeholders of local authorities, police forces, fire and rescue services, vehicle manufacturers, motorists and their families and friends?

So, given the approach of F1 to reduce risk of death and serious injury, how close to Vision Zero are they? The last death during a race was Ayrton Senna back in 1994 in the same weekend as Roland Ratzenberger was killed in qualifying. There have been three marshalls killed in the last 21 years – each incident leading to changes in safety fencing or vehicle design (to stop wheels detaching). There have been serious incidents, with drivers breaking legs or when Massa suffered a head injury when a piece of Barrichello’s car hit Massa’s helmet back in 2009. Hopefully Bianchi’s injuries will not prove to be fatal and the record of the last 20 years with zero driver deaths on race day can be sustained.

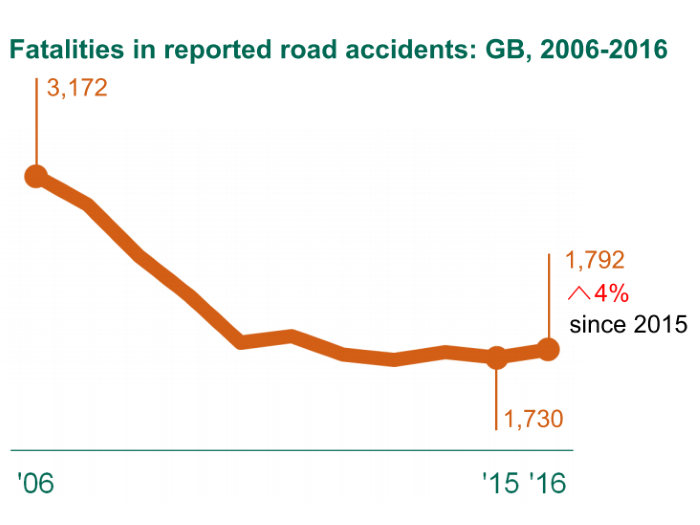

But how does that compare to deaths on Britain’s roads? Each year, there are about 60,000 F1 driver miles driven on race days (so excludes testing, practice and qualifying miles) equating to about 1.2 million F1 driver miles driven since 1994. And in that time, there has been one death. However, given the miles driven on GB roads, this actually equates to a F1 fatality rate per billion vehicle miles that is about 100 times higher than that of the public. Perhaps this isn’t surprising, given the speeds that F1 drivers achieve and the manoeuvres they make in order to win races. What it does show, though, is that the message that motorsport is dangerous does hold true and that their work to reduce risk as much as possible is a necessary one.